Biology is the natural science that studies life and living organisms, including their physical structure, chemical processes, molecular interactions, physiological mechanisms, development and evolution. Despite the complexity of the science, certain unifying concepts consolidate it into a single, coherent field. Biology recognizes the cell as the basic unit of life, genes as the basic unit of heredity, and evolution as the engine that propels the creation and extinction of species. Living organisms are open systems that survive by transforming energy and decreasing their local entropy to maintain a stable and vital condition defined as homeostasis.

Biology deals with the study of life and organisms.

top: E. coli bacteria and gazelle

bottom: Goliath beetle and tree fern

Sub-disciplines of biology are defined by the research methods employed and the kind of system studied: theoretical biology uses mathematical methods to formulate quantitative models while experimental biology performs empirical experiments to test the validity of proposed theories and understand the mechanisms underlying life and how it appeared and evolved from non-living matter about 4 billion years ago through a gradual increase in the complexity of the system.

Etymology

“Biology” derives from the Ancient Greek words of βίος; romanized bíos meaning “life” and -λογία; romanized logía (-logy) meaning “branch of study” or “to speak”. Those combined make the Greek word βιολογία; romanized biología meaning biology. Despite this, the term βιολογία as a whole didn’t exist in Ancient Greek. The first to borrow it was the English and French (biologie). Historically there was another term for “biology” in English, lifelore; it is rarely used today.

The Latin-language form of the term first appeared in 1736 when Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus (Carl von Linné) used biologi in his Bibliotheca Botanica. It was used again in 1766 in a work entitled Philosophiae naturalis sive physicae: tomus III, continens geologian, biologian, phytologian generalis, by Michael Christoph Hanov, a disciple of Christian Wolff. The first German use, Biologie, was in a 1771 translation of Linnaeus’ work. In 1797, Theodor Georg August Roose used the term in the preface of a book, Grundzüge der Lehre van der Lebenskraft. Karl Friedrich Burdach used the term in 1800 in a more restricted sense of the study of human beings from a morphological, physiological and psychological perspective (Propädeutik zum Studien der gesammten Heilkunst). The term came into its modern usage with the six-volume treatise Biologie, oder Philosophie der lebenden Natur (1802–22) by Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus, who announced:

The objects of our research will be the different forms and manifestations of life, the conditions and laws under which these phenomena occur, and the causes through which they have been affected. The science that concerns itself with these objects we will indicate by the name biology [Biologie] or the doctrine of life [Lebenslehre].

History

Main article: History of biology

A drawing of a fly from facing up, with wing detail

A Diagram of a fly from Robert Hooke’s innovative Micrographia, 1665

Ernst Haeckel’s pedigree of Man family tree from Evolution of Man

Ernst Haeckel’s Tree of Life (1879)

Although modern biology is a relatively recent development, sciences related to and included within it have been studied since ancient times. Natural philosophy was studied as early as the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indian subcontinent, and China. However, the origins of modern biology and its approach to the study of nature are most often traced back to ancient Greece. While the formal study of medicine dates back to Pharaonic Egypt, it was Aristotle (384–322 BC) who contributed most extensively to the development of biology. Especially important are his History of Animals and other works where he showed naturalist leanings, and later more empirical works that focused on biological causation and the diversity of life. Aristotle’s successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany that survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to the plant sciences, even into the Middle Ages.

Scholars of the medieval Islamic world who wrote on biology included al-Jahiz (781–869), Al-Dīnawarī (828–896), who wrote on botany, and Rhazes (865–925) who wrote on anatomy and physiology. Medicine was especially well studied by Islamic scholars working in Greek philosopher traditions, while natural history drew heavily on Aristotelian thought, especially in upholding a fixed hierarchy of life.

Biology began to quickly develop and grow with Anton van Leeuwenhoek’s dramatic improvement of the microscope. It was then that scholars discovered spermatozoa, bacteria, infusoria and the diversity of microscopic life. Investigations by Jan Swammerdam led to new interest in entomology and helped to develop the basic techniques of microscopic dissection and staining.

Advances in microscopy also had a profound impact on biological thinking. In the early 19th century, a number of biologists pointed to the central importance of the cell. Then, in 1838, Schleiden and Schwann began promoting the now universal ideas that (1) the basic unit of organisms is the cell and (2) that individual cells have all the characteristics of life, although they opposed the idea that (3) all cells come from the division of other cells. Thanks to the work of Robert Remak and Rudolf Virchow, however, by the 1860s most biologists accepted all three tenets of what came to be known as cell theory.

Meanwhile, taxonomy and classification became the focus of natural historians. Carl Linnaeus published a basic taxonomy for the natural world in 1735 (variations of which have been in use ever since), and in the 1750s introduced scientific names for all his species. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, treated species as artificial categories and living forms as malleable—even suggesting the possibility of common descent. Although he was opposed to evolution, Buffon is a key figure in the history of evolutionary thought; his work influenced the evolutionary theories of both Lamarck and Darwin.

Serious evolutionary thinking originated with the works of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who was the first to present a coherent theory of evolution. He posited that evolution was the result of environmental stress on properties of animals, meaning that the more frequently and rigorously an organ was used, the more complex and efficient it would become, thus adapting the animal to its environment. Lamarck believed that these acquired traits could then be passed on to the animal’s offspring, who would further develop and perfect them. However, it was the British naturalist Charles Darwin, combining the biogeographical approach of Humboldt, the uniformitarian geology of Lyell, Malthus’s writings on population growth, and his own morphological expertise and extensive natural observations, who forged a more successful evolutionary theory based on natural selection; similar reasoning and evidence led Alfred Russel Wallace to independently reach the same conclusions. Although it was the subject of controversy (which continues to this day), Darwin’s theory quickly spread through the scientific community and soon became a central axiom of the rapidly developing science of biology.

The discovery of the physical representation of heredity came along with evolutionary principles and population genetics. In the 1940s and early 1950s, experiments pointed to DNA as the component of chromosomes that held the trait-carrying units that had become known as genes. A focus on new kinds of model organisms such as viruses and bacteria, along with the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA in 1953, marked the transition to the era of molecular genetics. From the 1950s to the present times, biology has been vastly extended in the molecular domain. The genetic code was cracked by Har Gobind Khorana, Robert W. Holley and Marshall Warren Nirenberg after DNA was understood to contain codons. Finally, the Human Genome Project was launched in 1990 with the goal of mapping the general human genome. This project was essentially completed in 2003, with further analysis still being published. The Human Genome Project was the first step in a globalized effort to incorporate accumulated knowledge of biology into a functional, molecular definition of the human body and the bodies of other organisms.

Foundations of modern biology

Cell theory

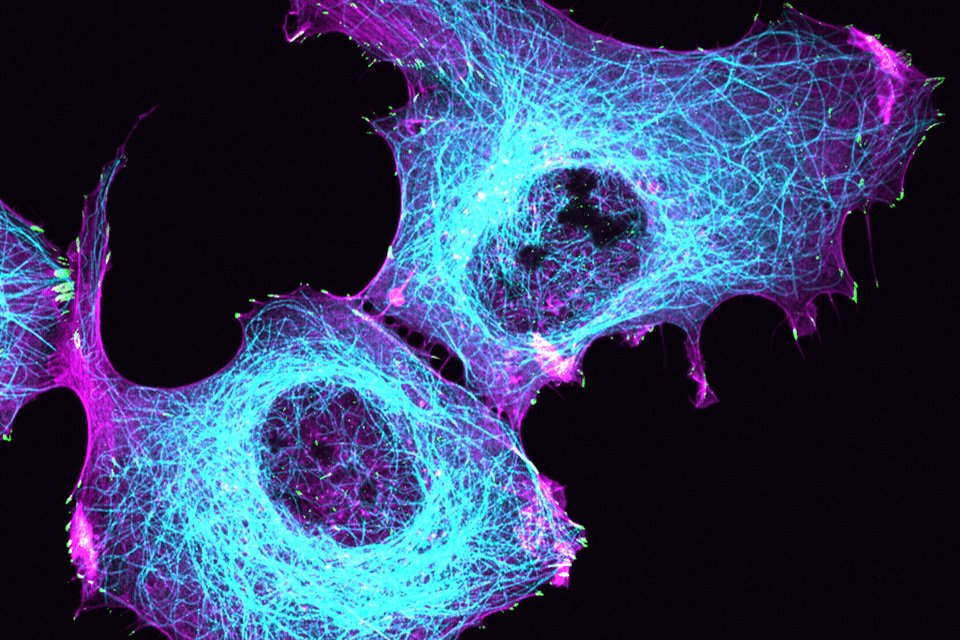

HeLa cells stained with Hoechst blue stain.

HeLa cells with nuclei (specifically the DNA) stained blue. The central and rightmost cells are in interphase, so the entire nuclei are labeled. The cell on the left is going through mitosis and its DNA has condensed.

Main article: Cell theory

Cell theory states that the cell is the fundamental unit of life, that all living things are composed of one or more cells, and that all cells arise from pre-existing cells through cell division. In multicellular organisms, every cell in the organism’s body derives ultimately from a single cell in a fertilized egg. The cell is also considered to be the basic unit in many pathological processes. In addition, the phenomenon of energy flow occurs in cells in processes that are part of the function known as metabolism. Finally, cells contain hereditary information (DNA), which is passed from cell to cell during cell division. Research into the origin of life, abiogenesis, amounts to an attempt to discover the origin of the first cells.

Evolution

diagram showing Natural selection favoring predominance of surviving mutation

Natural selection of a population for dark coloration.

Main article: Evolution

A central organizing concept in biology is that life changes and develops through evolution, and that all life-forms known have a common origin. The theory of evolution postulates that all organisms on the Earth, both living and extinct, have descended from a common ancestor or an ancestral gene pool. This universal common ancestor of all organisms is believed to have appeared about 3.5 billion years ago. Biologists regard the ubiquity of the genetic code as definitive evidence in favor of the theory of universal common descent for all bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (see: origin of life).

The term “evolution” was introduced into the scientific lexicon by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in 1809, and fifty years later Charles Darwin posited a scientific model of natural selection as evolution’s driving force. (Alfred Russel Wallace is recognized as the co-discoverer of this concept as he helped research and experiment with the concept of evolution.) Evolution is now used to explain the great variations of life found on Earth.

Darwin theorized that species flourish or die when subjected to the processes of natural selection or selective breeding. Genetic drift was embraced as an additional mechanism of evolutionary development in the modern synthesis of the theory.

The evolutionary history of the species—which describes the characteristics of the various species from which it descended—together with its genealogical relationship to every other species is known as its phylogeny. Widely varied approaches to biology generate information about phylogeny. These include the comparisons of DNA sequences, a product of molecular biology (more particularly genomics), and comparisons of fossils or other records of ancient organisms, a product of paleontology. Biologists organize and analyze evolutionary relationships through various methods, including phylogenetics, phenetics, and cladistics. (For a summary of major events in the evolution of life as currently understood by biologists, see evolutionary timeline.)

Evolution is relevant to the understanding of the natural history of life forms and to the understanding of the organization of current life forms. But, those organizations can only be understood in light of how they came to be by way of the process of evolution. Consequently, evolution is central to all fields of biology.

Genetics

two by two table showing genetic crosses

A Punnett square depicting a cross between two pea plants heterozygous for purple (B) and white (b) blossoms

Main article: Genetics

Genes are the primary units of inheritance in all organisms. A gene is a unit of heredity and corresponds to a region of DNA that influences the form or function of an organism in specific ways. All organisms, from bacteria to animals, share the same basic machinery that copies and translates DNA into proteins. Cells transcribe a DNA gene into an RNA version of the gene, and a ribosome then translates the RNA into a sequence of amino acids known as a protein. The translation code from RNA codon to amino acid is the same for most organisms. For example, a sequence of DNA that codes for insulin in humans also codes for insulin when inserted into other organisms, such as plants.

DNA is found as linear chromosomes in eukaryotes, and circular chromosomes in prokaryotes. A chromosome is an organized structure consisting of DNA and histones. The set of chromosomes in a cell and any other hereditary information found in the mitochondria, chloroplasts, or other locations is collectively known as a cell’s genome. In eukaryotes, genomic DNA is localized in the cell nucleus, or with small amounts in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid. The genetic information in a genome is held within genes, and the complete assemblage of this information in an organism is called its genotype.